I Was Racially Taunted on Television. Wasn’t I?

New York Times

May 18, 2019

By Doug Glanville

Bigotry thrives in vagueness. It can be cowardly with double meanings.

Ambiguity has always been a friend to racism.

On May 7, during a television broadcast of a Chicago Cubs game at Wrigley Field, I was on camera doing in-game commentary for NBC Sports Chicago when, unbeknown to me, a fan behind me wearing a Cubs sweatshirt made an upside-down “O.K.” sign with his hand.

The meaning of this hand gesture can be ambiguous. It has long been used to simply say, “O.K.” Some people also use it to play the “circle game,” where you hold your hand below your waist and try to get others to look at it. And most recently it has been co-opted to express support for white supremacy. The man accused of committing the New Zealand mosque massacres flashed this sign during his first court appearance.

Because I am a person of color, the fan’s gesture suggested its sinister meaning.

I learned what had happened during my customary Uber ride from Wrigley Field to the local NBC studio to do the postgame show. I was checking my Twitter account, looking to banter with Cubs fans about the game as I usually do, but my feed was overrun by strange avatars, unrecognizable handles, aggressive trolls and a heated debate about racist imagery.

Many on Twitter said the Cubs fan intended for the gesture to be a racist sign. But many disputed this, some mentioning the circle game and some posting pictures of black people like Barack Obama and the basketball star Kevin Durant flashing “O.K.” signs. Because the gesture’s meaning was ambiguous, many argued, people were overreacting and playing the “race card.” Although I could not assess the fan’s intent, I was not swayed by these innocent explanations, because with symbols, context matters.

The Chicago Cubs organization entered into the fray before I managed to put all this together myself. It swiftly announced that it was investigating the matter and would punish the fan if necessary.

The next day I issued a public statement. I said that I was aware of the incident and of the possible connection to white supremacy, and that I supported the Cubs in conducting an investigation. I made sure to note that I would not say anything more until after the investigation was concluded.

Later that day, the Cubs completed their investigation and banned the fan from Wrigley Field indefinitely. They apparently determined that there was sufficient evidence to conclude the fan’s intentions were malicious.

But of course the gesture itself remains ambiguous, and so debate continues to rage on. It is worth noting that this is precisely why racists embraced the gesture in the first place. According to the Anti-Defamation League, users of the online message board 4chan originally introduced the idea that the “O.K.” sign was a white supremacist symbol as a prank to get the media to overreact to innocuous gestures — but the sign soon morphed into a genuine expression of white supremacy as well.

Ambiguity, as I say, has always been a friend to racism.

In the court of public opinion, ambiguity cuts two ways. With something as inflammatory as racism, we often project our biases in ways that shape how we see a vague situation, initially leading to opposing viewpoints where each one dogmatically sees itself as truth. The middle ground evaporates into thin air.

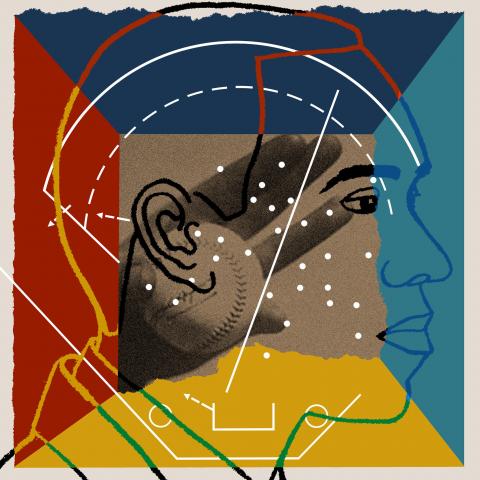

The communication breakdown here can be illustrated by imagining a coordinate graph on which you plot what you understand to be the racist episodes you experience or hear about during your life. The x-axis represents the passage of time and the y-axis represents the degree of racism of an episode — from someone’s assumption that you’re a valet when you’re parking your own car to the burning of a cross on your lawn. For each experience, you mark a dot.

Over time, the dots accumulate, and you start to see a pattern. You draw a curve that connects the dots and you develop a keen sense of things that happen to you because of your race. The pattern allows you to notice correlations, to make predictions. You are learning from evidence, in part for your self-preservation.

Now imagine someone plotting a graph who encounters such episodes from a more privileged or isolated perspective. Maybe this person hears about them only if they are sensational enough to make the news. He sees evidence of racism only from time to time, and when he does, it tends to be stark and unambiguous — the use of racial slurs, an explicit avowal of hate.

This person’s graph has many fewer dots, with larger spaces between them. There is no curve he is able to draw. No pattern presents itself. Racism seems to him to be a rarity, maybe even invented.

How do I talk with this person and convince him of the pattern I see? What makes my curve real in light of his points? If I draw his attention to an episode that is not overtly racist, he may think it reasonable to dismiss it as an “isolated incident,” to accuse me of seeing things that don’t really exist. Why jump to conclusions? Why play the race card? He may tell me that racism wouldn’t be such a problem if I didn’t keep bringing it up.

I come to the debate about the Cubs fan’s “O.K.” gesture with a strong personal experience of how racism works in our country. I realize that this does not make the fan guilty of racism. But in the larger context, his guilt or innocence is not the whole story.

If you innocently decorate your office with a rope shaped into a noose because you like rodeo cowboys, I can still be offended. You can like rodeo cowboys; I can be upset. Both can be true. The fact that you like rodeo cowboys does not mean I am overreacting, nor does it make you a racist.

I should stress that I am optimistic about race in America. I grew up in the 1970s and ’80s in Teaneck, N.J., which voluntarily desegregated in the early ’60s. I had a racially diverse and inclusive educational experience through high school. I graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with an engineering degree and then played professional baseball for nine years, including two stints with the Chicago Cubs. I have stood proudly for the national anthem at thousands of baseball games.

I have found that most people of color try, as I do, to find an innocuous explanation when something bad happens to them. It is a terrible feeling to have to assume the worst of people, to accept that much of the world thinks you are less worthy simply because of the color of your skin. It is far more comforting to find another reason, a more “rational” one.

But you cannot ignore the data, the curve on the graph. Racism’s most prevalent form is subtle and stealthy, and it is no less insidious for it. Yes, I can be wrong about whether a particular ambiguous episode is racist. One point does not make a curve, and one curve does not make a point. An “O.K.” sign means nothing on its own. But racism thrives in ambiguity, in shadows. In this form, it is cowardly with double meanings.

Ambiguity can make people of color feel that their sanity hinges on a single verdict. If the Cubs fan was flashing a white nationalist sign, we are in danger; if he was not, we are “politicizing” things or “race-baiting.” This is an incapacitating position to find yourself in, especially when you are just an innocent bystander. You are now forced to redundantly relitigate the existence of racism from a defensive position.

This is why, whether the Cubs fan is innocent or guilty, my life does not just “go on.” I do not have the luxury to decide when I am done talking about racism, because I have to live with it. The public will eventually lose interest in this controversy; the Cubs can return to their bullpen questions. There can be a collective sigh of relief that racism is a topic we don’t have to discuss anymore; we can even declare ourselves “post-racial.”

If the Cubs fan is innocent, he will be O.K. That would be the just outcome. But racism will remain. Being wrongfully accused, while unfair, is not the same as living a life where your skin color automatically makes you a target. Being on guard about hate is not “political.” It is a matter of simple self-protection.

Symbols are the easy part of racism to endure. Racism is not just a symbol or a feeling; it also is a system. It is institutional power that can crush neighborhoods, generations of children, stripping people of validation, self-worth and opportunity. Those who have been subjected to this misuse of power are never certain that they will be O.K.

If the Cubs fan is guilty, we still have a choice in what that means to us and what we can do about it. There were tens of thousands of other fans at that game, most of whom were there as one baseball family. We can focus on a single fan and build our cases against one another, or we can focus on everyone else and build understanding together. There is a choice.

I hope we choose the path of empathy and unity. The Cubs fan was wearing the same logo that I wore when I first realized my dream of playing major league baseball. That should have made him an ally, not an enemy. After all, the game of baseball is played by teams of people from all walks of life, following universal rules, competing on a level playing field. That may be partly mythology, but it can serve as an aspirational ideal, a goal for us as a society.

To achieve that goal, we need to acknowledge racism, and acknowledge that it operates not only with fire hoses and police dogs but also in whispers, in fine print, in invisible ink, in coded language. Until we are fully against it, we are letting it fester, and while we try to sort out the ambiguities, people are suffering. And they will still suffer once we have our answers, no matter what we find out.

Republished from The New York Times

Photo Credit: Lucy Jones for The New York Times