Perfect Together

The New York Times

June 15, 2012

By Doug Glanville

Every player knows that there are accomplishments in baseball that might seem personal, yet in fact they belong not to the individual but to the history and legacy of the game itself. Twirling a no-hitter, hitting for the cycle, the grand slam, the perfect game. None of these is meant to be just another tick on a résumé; they’re for the game to own. These markers are much bigger than the players who, technically, accomplished them.

This season there have already been five no-hitters, a pace that would shatter the modern-era record of seven thrown in both 1990 and 1991. The most recent was Matt Cain’s perfect game for the San Francisco Giants against the Houston Astros on Wednesday night. Before that was Philip Humber of the White Sox (another perfect game), Jered Weaver of the Angels, Johan Santana of the Mets and, just last week, the Seattle Mariners — six of whom pieced one together, with five relievers following the starter, Kevin Millwood, who went down to injury.

What the Mariners pulled off as a team shows how a no-hitter (or a moment like it) is really embedded in the fabric of the game. Using six pitchers to throw one is unusual, but it probably reflects more accurately what truly makes up a no-hitter. Johan Santana may have thrown the first pitch and the last pitch of his no-hitter, but it was more than a solo achievement: Mike Baxter had to make a super catch, the umpire had to miss a call, every Met defender had to be in the right place at the most opportune moments. Santana can only make a pitch, and no matter how good that pitch is, it has to be fielded by his defense or caught by his catcher. Without all of them, a no-hitter is an illusion.

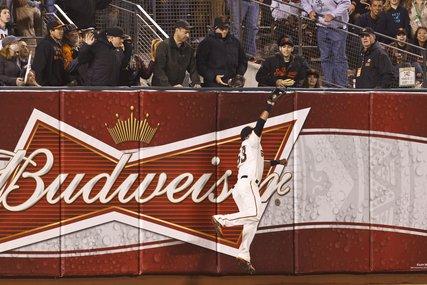

This week, Cain benefited from a running catch by the left fielder, Melky Cabrera, in the sixth inning and a sensational diving grab by the right fielder, Gregor Blanco, in the seventh, both of which preserved perfection. No matter what no-hitter story you choose, there is always heroic help to turn one of these games into more than just another well-pitched effort.

I remember a game when I was playing center field for the Phillies and our pitcher had a no-hitter going in the ninth inning. A ball was hit my way, I got a bad read on it and was unable to recover in time to make the catch. The no-hitter was gone.

I was promptly booed. It was a home game, too, and at the time it was hard not to take the fans’ dissatisfaction personally. (My teammates were not happy either, even though they knew it was a play I had made previously in my career.) True, the fans were not there to see a no-hitter per se — just as you may not have been there specifically to find that $100 bill on the sidewalk — but they knew they could have been very pleasantly surprised to find themselves cruising arm in arm with the game’s divine powers of inspiration. Instead, when that game was wrapped neatly in its box score, it was easy to deduce that I was the key factor that prevented them from witnessing one of baseball’s great snapshots.

As a player, you are humbled just by being able to participate in creating these moments. Every pitcher, every hitter knows which the special ones are, and knows that they require much more than a rocket arm or lightning-quick hands. It’s almost as if there’s a magic wand at work, one that has the shortstop in the right position or the wind blowing just in the right direction. It cannot happen in any other fashion.

Another thing to keep in mind: In baseball, we accept that even in a perfect game, a pitcher will throw 25 percent or more of his pitches outside the strike zone, sometimes wildly so. Cain threw 39 balls out of 125 pitches en route to his perfect game. In no way is a pitcher ever as “perfect” as perfect can be, but within the very human rules of baseball, it qualifies.

Jered Weaver pitched his no-hitter with his family in the stands. Afterward, with tears in his eyes, he found his father and hugged him as if he were a 4-year-old boy tall enough only to grab one leg. He was able to embrace his history, knowing that nothing happens without it.

Santana had an additional perspective: simply playing the game at all was out of his reach for a time. Injuries had put his career in doubt, and he had to work his way back to health just to have the chance to record a single out, let alone 27 of them without yielding a hit. I am sure that after he got that final out, he was humbled by how much bigger his no-hitter was even than the gift he received when the gods first tapped his left arm.

These achievements may end up on one player’s résumé, but when we reflect on the happenstance and the collective effort (human and divine) it took to get there, we come to accept that they are Olympic in stature and therefore for all of us to cherish.

Republished by The New York Times

Photo Credits: Jason O. Watson/Getty Images, Jeff Chiu/Associated Press