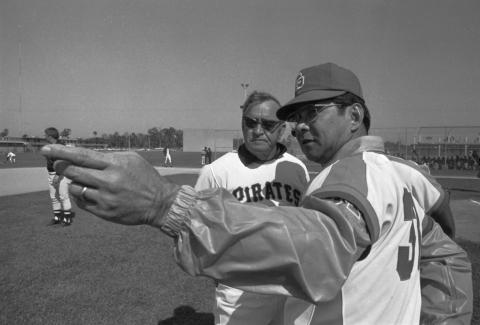

Remembering Wally Yonamine

The Atlantic

February 28, 2016

by Doug Glanville

The Japanese American athlete, who died five years ago, played a significant role in restoring trust between the two countries after World War II.

In the summer of 2000, at an airport in Honolulu, Kaname “Wally” Yonamine was explaining an exhibit that outlined his legacy of playing baseball in Japan in the 1950s to his granddaughter and a curious bystander. The bystander was fascinated, so much so that he wanted to take a picture of the display. But unaware he was in Mr. Yonamine’s presence, he asked him to step aside so he wouldn’t be in the picture.

Wally Yonamine said nothing.

It’s this humility, along with his extraordinary achievements in baseball and football, that made Yonamine—who died five years ago, on February 28, 2011—one of the most remarkable figures in 20th-century sports. Born in Hawaii to Japanese parents, he was the first Asian player to play professional football in the U.S, spending a season with the 49ers in 1947. He is also considered the first American to play professional baseball in Japan after World War II, making him one of the most significant and underappreciated figures in Japanese American diplomacy.

After the devastating atomic bombs in the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima brought World War II to a swift end, Allied forces occupied Japan until 1952. Yonamine was considered a natural ambassador to help repair the relationship between the two countries, but the unique suspicion toward Americans in Japan at the time didn’t preclude those with Japanese heritage. The wounds of the war were fresh, and anyone intimately engaged in Japanese society and culture from the United States (particularly if they were of Japanese descent) had to work to be trusted.

Yonamine’s orders, approved by the then Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, were simple: Go to Japan and play baseball, a celebrated national sport. With no formal command of the language or the intricacies of the culture, he dove in.

He made his professional debut in Japan in 1951, having earned himself a spot with the Yomiuri Giants. He had to adjust to a number of new factors: the food the team ate, how they traveled, the etiquette of practice, how to communicate with the manager, the hierarchy. All of it required time, and more importantly, a humble soul. Yonamine had to prove that as a teammate he could accept these traditions and rituals with an open mind.

To his credit, he adapted to team culture without trying to change it. He honored it, followed its rules, and endured hazing, which over time, led to him gaining his team’s acceptance, and ultimately something even more valuable: its respect. Once he gained the latitude to have more of a voice on the field, he played with reckless abandon, employing an aggressive style on the bases.

Robert Fitts, the author of the biography Wally Yonamine, The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball, explains Yonamine’s influence on the field. “Before he came,” Fitts says, “they played a passive brand of ball. The Japanese were shocked the first time Yonamine took out the pivot man on a double play, but soon his teammates, and then their opponents, began to imitate him.”

As Yonamine rose in the ranks, he never took his excellence for granted. On days off, instead of taking a well-earned break, he would work out with the minor-league team, often bringing his family along. If he didn’t get the results that he was looking for in the game, he would lean into a pitch from time to time to get hit intentionally just so he could get on base.

It wasn’t long before he’d earned the trust to mentor younger players, which sparked his passion for coaching and teaching the next generation. The legendary homerun hitter, Sadaharu Oh, got his big break after Yonamine was already established as a veteran player. Oh was a good young hitter who didn’t have a strong defensive position. Yonamine, as his teammate on the Yomiuri Giants, saw that Oh’s best position was the same as his, first base, so he suggested to the coaches that he play the outfield to help get Oh’s bat in the lineup. Oh would go on to hit a world record 868 home runs, and win nine championships, five batting titles, and two triple crowns.

Yonamine retained the longest consecutive tenure of anyone in the history of Japanese baseball. His life in Japan spanned 38 years between playing, coaching, and managing. During that time, he won eight pennants, three batting titles, and an MVP award in 1957. A lifetime .311 hitter, he was inducted into the Japanese Hall of Fame in 1994, the first American to achieve that honor.

Even after he achieved great success, Yonamine was never complacent. As a father, he stressed the importance of education to his children, which he believed limited the amount that luck would drive their futures. Growing up in extreme poverty, he knew great sacrifice. He was once shot at when he was young for trying to steal a watermelon from a nearby farm. He also rejected a football scholarship to Ohio State University so he could help put food on the table for his family. He always regretted not having the chance to receive a formal education and because he knew he had to depend on his body for his career, he ate healthily and trained vigorously.

But family came first. “During the season, whenever he could, he would sneak off to come home,” his daughter Amy recalls. “When my sister Wallis was born, he was devastated that the manager warned him that he needed to be on that team bus instead of with his wife. The manager said to him, ‘Are you a midwife?’”

Nevertheless, when Yonamine was coaching the Chunichi Dragons, he would bring his kids out to the team city of Nagoya by bullet train from Tokyo for extended stays when school was out in the summer. Amy recalls how those visits slowly transformed coaching culture, to the point where other coaches would soon start bringing their families for the summer, too.

“People who had to abide by the idea that work always came before family began to see how powerful it was to be with family around work,” she says.

Many have referred to Yonamine as the Jackie Robinson of Japan. But he never fully accepted the comparison, saying, “Robinson had it tougher.” He had a great respect for Robinson and all of the change that came behind him in the ’60s. But Yonamine’s influence on baseball and on improving relations between the U.S. and Japan is hard to deny. In 1998 he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure by the Emperor of Japan for his efforts in diplomacy.

It was his experiences on the road as an athlete in the U.S. that crystallized his commitment to equality. On one particular trip, as the black players headed one way to their accommodations after a game, and the white players headed another, he was left standing in the middle, until finally a white player said to him, “Wally, you are with us.”

In these moments, diplomacy entered his blood, prompting him to seek ways for everyone to be on the same team, regardless of their color or heritage, as equals. Throughout his career, he brought people together by making them feel not just like part of his team, but part of his family.

Republished from The Atlantic.

Photo Credit: Associated Press

Source:

Other