When It Was More Than a Game

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

August 6, 2011

By Doug Glanville

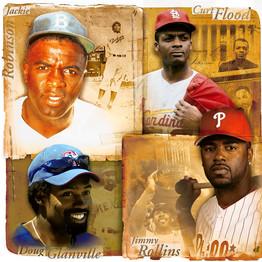

Jackie Robinson had to be a saint—Jimmy Rollins can just play ball Curt Flood had it tough.

After being traded away from the St. Louis Cardinals—a team he did not want to leave—in late 1969, the outfielder challenged Major League Baseball's reserve clause, a relic of baseball's earliest years that allowed teams to hold on to players in virtual perpetuity. Flood's case made it all the way to the Supreme Court. But he lost, and the fight took its toll.

Many sportswriters and fans thought Flood was trying to bring down baseball and its traditions. An African-American man unafraid to compare the reserve clause to slavery, he was criticized sharply in the press for disloyalty and received surprisingly tepid support from civil-rights leaders. By the time the Supreme Court upheld the reserve clause, 5-3, in 1972, Flood was already out of the game. After taking on the baseball establishment, he was not the same ballplayer—he sat out the 1970 season and played only a few more games in 1971 before retiring. When a journalist tracked him down in 1978, he begged: "Please, please don't come out here. Don't bring it all up again. Please. Do you know what I've been through?"

A few years earlier, major leaguers had finally established a right to free agency, when Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith (two white players) won a 1975 arbitration ruling after playing a year without a contract. But Flood was the one who broke the mold—and paid the price. Is it a coincidence that an African-American player failed and lost his career while two white players succeeded? We can't know, but as an African-American, Flood suffered uniquely.

Curt Flood just wanted to play baseball and enjoy the same freedoms as almost every employed American. He didn't seek a role as representative of his race or embrace it in the manner of Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby (Robinson's less famous counterpart, who integrated the American League). But African-American athletes have long had little control over how they are perceived or how free they are in their reactions. During my own nine years as a professional baseball player, I was able to play the game at its highest level, to be a free agent and choose my employer, to say what I wanted when I wanted. None of this could have happened without men like Robinson, Doby and Flood—men who, because of the color of their skin, had to be better than the game they played.

Any high-performance athlete has been trained since childhood to thrive in the face of conflict: Competition, in all its glory or ignominy, requires perseverance, dedication, drive and self-confidence. But when the game ends, the athlete faces an everyday existence for which he may not be as well-equipped. This is especially true of African-American athletes who, as Gerald Early shows in his small, powerful book "A Level Playing Field," face off-the-field challenges that can be far more daunting than those they face on game day. Mr. Early illuminates in great detail the inner collisions of African-American athletes as they find their way in the (mostly white) public sphere. His is a valiant—and largely successful—attempt to explain what it's like to be an African-American athlete today.

The book consists of six essays—three originally delivered as talks at Harvard in 2004 and three written expressly for this book, developing the themes of the lectures—that trace the experience of the African-American athlete over the latter half of the 20th century. In addition to an acute account of Flood's experience, Mr. Early provides a perceptive analysis of the 2003 controversy that surrounded Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Donovan McNabb—a black star at a position still predominantly played by white athletes—following commentator Rush Limbaugh's claim that Mr. McNabb was overrated by white liberals who wanted him to succeed.

But the core figure of the book is Jackie Robinson, who inspires three essays and pervades all the rest. The opening essay examines the behavior of Robinson, not just when faced with racist taunts during his inaugural campaign of 1947 but later, when he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee about loyalty among African-Americans. Robinson walked a tight rope: While renouncing political philosophies that worked against what makes America great, he supported freedom of expression, especially in a country that compromised its ideals by treating African-Americans as second-class citizens. The author contrasts this testimony with that of another multitalented African-American, the strident communist Paul Robeson.

Another essay compares the way Robinson was perceived by both whites and African-Americans with the later experience of other athletes, such as Muhammad Ali, and to contemporary African-American athletes. In the course of six decades, he points out, African-American athletes have come to virtually dominate such sports as basketball, football and boxing—though not, notably, baseball. That anomaly is the subject of a final, brief reflection, "Where Have We Gone, Mr. Robinson?," which wonders if Jackie "would be disappointed to know that a relatively small number of African-Americans remain drawn to the game that he transformed."

When Robinson broke Major League Baseball's color line in 1947, he showed that America could embrace all people in the same arena—a celebration of the country's ideals. At the same time, the tension-filled ordeals of that inaugural campaign demonstrated how far America needed to go. Robinson had to play with enthusiasm and genius while never fighting back against attacks aimed at himself, his family and everything he represented.

Mr. Early recognizes that not every player can be Jackie Robinson. But he suggests that Robinson's life can serve as a useful lens through which to study the experience of any African-American athlete. Mr. Early encourages us to think of high-performance athletes as what he calls "hybrids"—that is, people who live in an ambiguous space between the public and private. Even today African-American athletes must master not only their sport but the difficult politics of the media and business worlds. Although they now have access to these elite institutions, they navigate uncertain waters, never fully comfortable, feeling a breath away from an unwelcoming committee.

For some, Jackie Robinson's saintly model of behavior may be a further burden. They may be ill-prepared by their backgrounds for the task of interacting with an overwhelmingly white establishment. (In Major League Baseball, there are no African-American owners, only three African-American general managers and only two African-American managers.) Other players may be trapped by ideas of "racial loyalty." Think of Michael Vick, who "kept it real" and elected not to draw away from negative elements within his circle, wanting to keep the acceptance level high from the people who were with him from day one. Two different worlds merged for him, and it is hard to stand in both.

Maintaining such a difficult balance places a player in solitude, a predicament that Mr. Early refers to as "Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside": a person who reassures white authority yet by his very presence undermines it, being not black enough to be black yet not "not black" enough to be white. An excellent example is Donovan McNabb.

Quoting news coverage, Mr. Early shows how the controversy over Mr. Limbaugh's 2003 comments quickly shifted from one about sports to one about affirmative action, with factions adopting familiar arguments. Mr. Early is less interested in these debates than in both sides' presumptions regarding the popular construct of the "black quarterback"—an athlete with supposedly different skills than a white one (running rather than passing, primarily). A local Philadelphia leader of the NAACP, Mr. Early notes, "harshly criticized McNabb for lacking racial pride for wanting not to be stigmatized as a 'black quarterback.' "

Mr. Limbaugh eventually resigned from his post at ESPN, and the controversy hindered his effort to become part of an NFL ownership group a few years later. But, interestingly, that was not the story's end. Earlier this year Mr. Limbaugh had the opportunity to spring to Mr. McNabb's defense, against charges that Mr. McNabb is "too white."

Bernard Hopkins, an African-American champion boxer, had criticized Mr. McNabb for his privileged upbringing in a Chicago suburb, suggesting that Mr. McNabb lacked a certain toughness. Mr. Limbaugh called such comments "horrible and distasteful," saying that Mr. McNabb's parents "are out there having to defend the way they raised him, and all they tried to do was give him opportunity after opportunity."

Mr. Limbaugh is surely as correct in this case as he was wrong before, but the entire controversy underscores Mr. Early's central point. Donovan McNabb simply can't make everyone happy. He is another example of an African-American athlete who stands for so many things that we can't even see him clearly. He represents a history, a race and a new possibility for the quarterback position, all wrapped up in one uniform. It's no coincidence, Mr. Early observes, that when Michael Vick returned to football after serving time in prison for his link to a dog-fighting ring, he did so with the Eagles, where he understudied for a season with Mr. McNabb as a role model.

For any African-American, being a role model means accepting the burden of representing your race. We should not be surprised that many athletes don't want that. It was another Philadelphia star, Charles Barkley, who went so far as to challenge the whole idea by boasting, in a Nike Air commercial: "I am not a role model." Agree or disagree with Mr. Barkley's position, the fact that he could openly express such a position at all was a gift from the past. A generation of trailblazers often had to stay silent in order to earn today's African-American players the latitude to be freer in their expression.

Mr. Early, of course, could not include every athlete we might wish in such a short book or mention controversies that have occurred since he completed it. What might Mr. Early make of Tiger Woods and his sudden (if temporary) exit from golf because of a personal scandal, at a time when he was the icon of a sport that African-Americans deemed irrelevant before his arrival? Mr. Woods refuses to be characterized as solely African-American, asserting a much broader heritage, but Mr. Early's book provides insight into his situation.

"A Level Playing Field" makes an excellent template from which to work when we want to look beyond the platitudes that mark the dialogue about race and sport. But it also reminds us how far we've come. By the time I broke into the major leagues in 1996, it had been almost 50 years since Jackie Robinson's first season. But I still felt the weight of the hybrid experience, holding my breath, knowing that I myself had rocked some boats as the first African-American Ivy League graduate to make it to the big leagues. I was cautious on some level, uncertain what to expect in the way of fair treatment.

I didn't even realize the burden I was carrying until five year later, when my Phillies teammate Jimmy Rollins entered the league. He was Rookie 2.0, an African-American comfortable in his own skin, tiptoeing around nothing at all. He was free to be who he was. Besides going on to win an MVP, Mr. Rollins became a Phillies institution, an achievement that suggests to me that our culture itself has hybridized enough to see a great player like Mr. Rollins as a part of the bigger picture of overall athletic excellence. This takes precedence, as it should, over the historically divisive and narrow lines of race, even if it does not eliminate them entirely. Such freedom from burdensome expectations gives any athlete who enjoys it entrée into limitless possibility, but best of all a chance to just play the game.

Republished from The Wall Street Journal